Crime Corner: The Phantom of Palouse

The Death of a Millionare

Locals may recall the ghost story that shook Whitman County to its core. Not many remember his name, but some will remember the stories of a man that seemingly disappeared without a trace while hopping from property to property.

People called this ghostly figure “The Phantom of Palouse.”

The Phantom would not be caught until the story of Whitman County’s missing millionaire unfolded in December 1964.

Whitman County Sheriff Mike Humphreys reported his close friend, Clarence E. Wittie, 54, missing on Jan. 2, 1960.

At the time, Clarence, nicknamed “Mickey,” was among the Palouse’s wealthiest wheat farmers and cattle grazers. He was known to don farmer-type overalls with a red bandana handkerchief in one hip pocket and a wallet in the other.

Clarence stayed on his family’s estate and remained a bachelor; eventually, he would absorb the 1,500 acres of wheatland and 500 acres of meadowland that his family-owned.

Sheriff Humphreys began to investigate the case and would soon discover that the last time Mickey was seen was in a conversation with his brother, Adam, along the roadway.

In an interview with Adam, Humphreys reported that Adam had expressed concerns about his brother’s disappearance.

Adam had ventured onto the family estate to find the front door unlocked. A molding pot of stew sat on the stove in the kitchen. Dirty dishes lay in the sink, and Mickey’s bed was unmade.

Adam said that had Mickey gone on a trip; he would not have left his home in such a condition. Not to mention, Mickey would only have traveled with clothing and personal belongings.

Sheriff Humphreys and Deputy Rice made a thorough search of the farmhouse. They did not find any sign of violence or a struggle. The outbuildings were also searched.

Had there been an accident, even involving a fatality, authorities would have checked the car’s license number and notified someone.

After interviewing Eva, Mickey’s sister, detectives found she had not seen or heard from her brother in more than a month.

The next stop was the bank in Oakesdale.

Banker Clarence Bawk had not seen Mickey in a month or two. He explained that Mickey arranged for all lease payments for his land to be made directly to the bank and credited to his account.

Mickey had started leasing his land for more than $2,000 a month. Bawk checked the account and found it to be more than $400,000.

He noted Mickey’s last withdrawal was $300 on Friday, Dec. 2. 1964.

The sheriff issued a missing person report describing Mickey and his car. Mickey was 54 years old, 5 feet 9 inches tall, and weighed about 190 pounds. He had light brown hair turning gray, blue eyes, and a ruddy complexion.

The clothing he had been wearing had yet to be discovered, but most likely had been bib overalls and a wool shirt. Ten days after the missing person report was sent out, Humphreys received a call from Spokane Police Capt. Orlan K. Sherar, who said Mickey’s vehicle had been located there, 50 miles north of the small town of Thorton, where the Witte estate was located.

The keys were still in the ignition, and the vehicle had been covered in the December snow for weeks.

The car was towed to the police impound for a laboratory examination, including a fingerprint check, microscopic examination for bloodstains, and interior vacuuming for foreign materials.

Sheriff Humphreys knew his friend was gone – nothing less than death could explain how Mickey would have abandoned his vehicle and disappeared without a trace.

The lab came up empty. There were no bloodstains and nothing to indicate what might have happened to the owner.

The investigation continued, and detectives closely monitored Mickey’s bank account. For five months, the case stood still – frozen. Not a single lead turned up.

On May 2, 1960, a hunter was drifting along the Spokane River in a boat near Nine Miles Falls, picking up driftwood. In an eddy, he found several logs and the body of a man.

The body was identified as a man that appeared to be in his 50s, dressed in bib overalls—a wire-bound the man’s wrists to an old automobile generator. Marks on the ankles suggested some broken loose binding had also weighted them.

The features of the victim were unrecognizable. Pathologists estimated the body had been submerged for several months. It was theorized that the cold water preserved the corpse during winter until the weight had broken loose and the body rose to the surface.

Capt. Allen checked the missing person reports and concluded the body may be Thorton’s missing millionaire. However, with the lack of flesh, fingerprints were out of the question for identification.

Police resorted to dental records and positively identified the remains as Clarence Witte.

The matter of death could not be determined. There was no evidence of poison, and body marks could not be identified as either stab or gunshot wounds. There were no broken bones.

Although no signs of struggle or violence were seen at the farmhouse, there were some indications that the slaying might have occurred there. The pot of beef stew on the stove, the dirty dishes, and the unmade bed suggested Mickey may not have planned to leave the house.

However, it also seemed very unlikely that the killer would have taken a corpse from Thorton to the Spokane River 50 miles away.

Sheriff Humphreys drew a blank, that is, until Spokane County detectives Walt King and Byron Franz offered Capt. Sherar a theory: What if the killer was “The Phantom of Palouse”?

“The Phantom of the Palouse” was a burglar that detectives had spent years tracking. The burglar only hit remote farms.

His modus operandi was peculiar, as he only burglarized homes when residents were away. He would stay at the property for a few days, sometimes in barns or mills. He would shower, wash clothes, make meals, and sleep in beds. He would strike every month or two.

He wouldn’t take anything except food or what money might be lying around. Jewelry, radios, guns, and other items that most burglars would target were ignored.

The Phantom might have watched Mickey leave his home, and when he returned, he was struck down.

Nearly five years later, on Nov. 15, 1964, a man full of liquor and remorse stumbled into police headquarters in Wenatchee and announced he was the long-sought “Phantom of the Palouse.”

He identified himself as Albert McKinney of Oakesdale, and he convinced detectives of his burglaries by providing detailed information about some 60 home burglaries in Whitman County.

McKinney confessed to his only non-residential burglary at Pacific Gas and Transmission Co. near Rosalia, where he stole $62 from the office on Sept. 4, 1964.

When McKinney was questioned about the Clarence “Mickey” Witte murder, he admitted to having known Clarence and Sheriff Humphreys as they grew up together.

McKinney said he had nothing to do with the murder. He could not provide an alibi for the night Mickey was murdered.

However, the following day, detectives received an anonymous call from someone reporting that they saw McKinney in the neighborhood when Candy Rogers disappeared and was killed. The Candice “Candy” Elaine Rogers murders held top priority for Spokane city and county law enforcement and the FBI.

She was 9 when she left home in Spokane to sell Camp Fire Girl mints in her neighborhood. She was missing for 16 days before her body was found Sunday, Mar. 22, 1959.

Reports say that she had been found 150 feet off the Old Trails Road, some seven miles northwest of Spokane, and she had been criminally assaulted and strangled by a strip taken from her slip.

McKinney was brought in for questioning immediately and provided an alibi, stating he was in Missoula, Mont., with a friend. He denied knowing the little girl.

Detectives located the friend McKinney said he was with and confirmed he had been in Missoula for some time that March. The friend reported that McKinney visited him occasionally and had even visited in late December, loaded with cash.

Detectives persisted and brought McKinney in for questioning again. For two days, McKinney denied having ever obtained such cash. However, soon after, detectives would present the community with a signed statement from Mckinney admitting to the murder of Clarence “Mickey” Witte.

McKinney knew that Mickey carried cash on him and was a wealthy man. He broke into the Witte estate on Dec. 17, 1959, intending to rob his childhood friend. Knowing that Witte was strong and could fight, McKinney armed himself with a club and a .32 caliber semiautomatic pistol.

Mickey was not home when McKinney broke in, so he hid in a shed and waited for him.

Mickey arrived at his home around 6:30 p.m. It was dark, and McKinney used this opportunity to sneak up on Mickey and strike him with the club. Mickey was still conscious as he tried to run. Two shots were fired in the night, and Mickey fell mortally wounded.

McKinney allegedly admitted to taking $500 from Mickey’s wallet and putting Mickey in the trunk of his vehicle. He would arrive in the city after midnight when he dumped the body near a bridge across the river. He later abandoned the vehicle and returned to the site of the body after stopping at a junkyard. He wired the dead man’s feet together and then the wrists, adding a generator for weight. He threw Mickey into the water.

Mickey had several charges filed against him, and he pleaded innocent in a preliminary hearing.

Note of Inflation: How Much Was Mickey’s Net Worth Today?

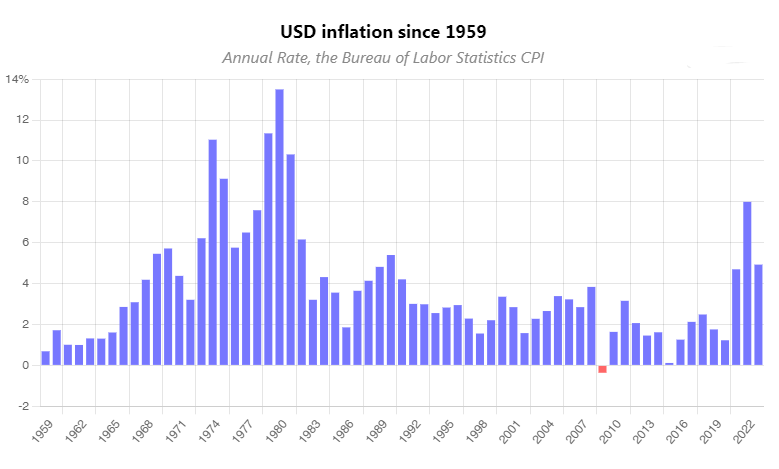

At the time of his murder in 1959, Clarence “Mickey” Witte had around $400,000 in his accounts. In 1959 this would have had the equivalent purchasing power of about $4,169,938.14 in 2023.

This is an increase of $3,769,938.14 over 64 years.

The dollar had an average inflation rate of 3.73% per year between 1959 and today, producing a cumulative price increase of 942.48%.

Graph of Inflation since 1959